Devils, Witches and Shucks of the Essex Saltmarsh

Alex Langstone

The Blackwater estuary is a vast expanse of tidal power, and is a shoreline littered with the ghosts of my ancestors. Here is a strand where the clandestine places of land and sea merge; punctuated with mysterious, secretive, and isolated islands. Osea, Mersea, Ramsey and Northey; Cobmarsh, Pewet and the Ray all sit on the water here, some now more accessible than others; due to land drainage and tidal flux. Here the highest tides bring overspill and nervous excitement that the old alluvial marshes are once more, creeping landwards, reclaiming their mysterious past.

The red ochre sails of traditional barges once plied their trade upon this waterway, which links land, river, and sea to generations of cultural traditions and interesting lore. This magnificent estuary where the river Blackwater meets the North Sea, is recognised as a Ramsar Wetland site of international importance.

It was here, on this eastern coast that in pre-Roman times the Celtic tribe of the Trinovantes held sway. Collaborators of Boudica and the Iceni, there isn’t much now to show they were here, but the ghosts of this lost British tribe survive deep within the land and on the tides.

These low lying and desolate salt marshes of the Essex shore are eerily beautiful in their bleakness. The marshy lip of the coastline between Brightlingsea and Maldon is particularly stunning and most definitely enchanted. This estuarial district of mid-Essex was once the hub of eighteenth-century smugglers, as barges could be sailed right to the head of the many creeks of the district, and Salcott Creek was at the centre of the illicit operations, where cargoes were unloaded and thrown into a marshy pool. The pool was actually a pond, which had been built with a false wooden bottom, which could be drained to retrieve the goods once it was safe to do so. Many of the old houses facing Salcott creek were lookouts for the illicit traders and hurricane lamps were put into top windows to warn that it was not safe to land.

Just to the west of Salcott lays the moated site of Devil’s Wood. This site is linked to the folklore of the Devil and Barn Hall. This traditional old Essex folk horror narrative is a classic example of diabolical devil lore, with layers of interesting themes to explore. The basic folk legend goes something like this -

One day, a local squire decided to build Barn Hall in what was known as Devil’s Wood. Soon after the builders had begun to dig the foundations on the small island in the centre of the wood, strange occurrences had begun. It was hoped that by building the new hall at this spot would forever thwart the Devil’s sabbaticals from gathering in their traditional meeting place. Each morning, when the builders returned, they found the trenches they had dug had been filled in. This went on for a few days, so in desperation, the squire ordered that a guard be put on duty during the night, to find out what was happening. On the first night the guard heard someone approaching.

"Who goes there!" he shouted. "I, Satan and my hounds," was the reply.

The guard replied, "This place is protected by God and me." The Devil and his hell hounds turned and fled. On the second night the Devil once more appeared. Again, the guardsman inquired as to who was there, and again Old Nick revealed himself and his pack of demon dogs. Only this time the guard made the mistake of declaring that only he was protecting the site, and not God. On hearing this, the Devil picked up a piece of building timber and declared “Wherever this timber falls, you shall build Barn Hall". The Dark Lord threw the timber high into night sky, and it twisted and turned over and over until it landed a mile or so to the west. The demon hounds then surrounded the guardsman, preventing any escape.

The Devil turned upon him, and with the hounds baying, ripped out his heart. The Devil then vowed that he would have the man’s soul whether he was buried inside the church or out. It was eventually decided that he should be buried within the church wall. There are those who say, that if you look closely, you can make out the Evil One's claw marks on the walls of All Saints parish church, where he tried in vain to search out his soul.

In the north wall of the church at Tolleshunt Knights you can still see an effigy of a knight holding his heart. The Devil’s hounds, incidentally, are said to haunt the nearby marshes on stormy nights, and the folklore of the Tolleshunt Knights Devil may indicate that we have recovered some lost wild hunt lore of the Essex coast, where the Devil and his demon hounds chase across the sky and into the grainy swamps of Salcott Creek. Here, under the light of the full moon and glistening stars, they continue to haunt the marshes and collect the lost souls of long dead bargees and fishermen of the past.

The beam, which the Devil threw up the hill was incorporated into the cellar of Barn Hall, which can apparently still be seen today. However, it would be an unwise to attempt to view it, as the Devil placed a curse on the beam, so that anyone who dared to enter the cellar would receive his deadly spell. Barn Hall was built at the beginning of the sixteenth century, so the tale can probably be traced back to this time, if not earlier.

The fields surrounding Devil’s Wood are believed to be haunted by strange beings. An account from the 1980s gives us a clue as to how the area can cause panic through its eerie reputation and unusual atmosphere.

The harvest had been completed, and the farmer was keen to get the field ploughed before the weather broke. He asked his son to plough the field into the evening, and the young farmer ended up using the powerful floodlights on the tractor to get the job finished. As the darkness of night fell across the land, the tractor driver began to glimpse movement along the edge of the field. At first, he thought that he was seeing a fox on her twilight hunt, but as he continued to plough his furrows, he began to feel very uneasy. He was convinced that he was being watched and he kept seeing and hearing movement close to his tractor. A large dark shape then cut across his path, and in a panic, he stalled the tractor. As he tried to restart the engine, he became aware that something unseen and malevolent was trying to open the tractor door; he turned the key again, now frantic to escape. The engine spluttered into life, and he headed off at full speed across the ploughed field. The tractor was bouncing around dangerously, but the young farmer wanted to get away from the terrifying dark field as soon as he could. He eventually reached the road and he headed home. The field was sold soon after this incident, and folk are still wary of driving past it at night.

The plough and sail village of Tollesbury lies on the northern bank of the Blackwater estuary and is almost completely surrounded by salt marsh, reed beds, creeks, fleets and saltings. This area is a truly wild part of the Essex shore, with little development, and is home to a huge variety of wildlife. Although once extinct, this part of the coast is now, once again, the domain of Marsh Harriers and Short-Eared Owls. At the end of the nineteenth century there were close on one hundred fishing smacks operating from Tollesbury Fleet, and oyster fishing was the main industry. The village has always been reliant on both the sea and the lands fringing the salt marsh for agriculture.

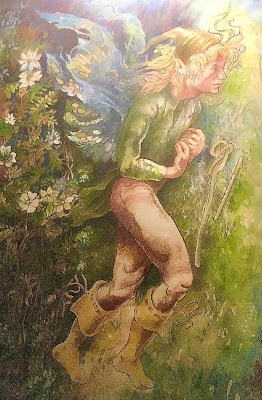

The old wind-blasted woods on the edge of the saltmarsh around Tollesbury are said to be ‘devil ridden’ and have been rumoured to have attracted the ghosts of many local witches and others practising the old folkways and magical arts. Related to this is the local ghost-lore of a phantom druid, who manifests once a month under the light of the full moon. During this time, he appears in all his ceremonial regalia in the woods on the edge of the mire.

Belief in witches and magic was still rife up to the beginning of the first world war, and the following accounts are from the early part of the twentieth century.

A local counter witchcraft charm was practised in and around Tollesbury, called branding the witch. This involved cutting a piece of your own toenail and placing it with a lock of hair from the person who had cursed you. These were both thrown into a fire. Immediately afterwards, you should place a poker into the fire, and allow it to get red hot. It was then slowly withdrawn from the flames, and as you did so, this would brand the witch and break the spell. The cursing culprit could then be identified, as he or she would show burn marks on their bodies.

Another counter witchcraft charm was used when someone had been ‘overlooked’ by a witch. You should light the copper and get the water almost to the boil. Set the ‘overlooked’ or ‘cursed’ person down by the water, and place one of their legs into it. You should get the person to keep the leg in as long as they could bear it. Then put them to bed. The following day the person was healed. However, the witch would be suffering with a scalded leg, so was identified.

Tollesbury folk had yet another way of identifying a witch. It was believed that if you saw a mouse and a cat eating from the same dish, the owner was a witch. Mice were favoured creatures of the Essex marsh wizards and witches, who kept them as familiars to help make magic. One Tollesbury sea witch was suspected of bewitching her son’s oyster smack. Each time he dredged for oysters, he would overshoot the spot. Unfortunately, there are no records of any names in this piece of sea-witch-lore. There was also a gypsy witch who travelled around the village, and at least two others who lived in the village, who had reputations as cunning folk, and were consulted about things strange and uncanny and children were warned not to look at the cottage where one of them lived.

The parish church of St Mary the Virgin sits upon the highest point in the village and parts of the building date from the eleventh century. The ancient churchyard is haunted by the ghost of a white rabbit which is reported to appear and run around the graves on some of the darkest nights of the year.

To the north-east, towards Brightlingsea, the Devil haunts the marshy promontory between Pyfleet Channel and South Geedon Creek. There was once an old weather-boarded shepherd’s cottage called ‘Found Out’ on the edge of the marsh. It sat by an old pond at the end of the old cart track from Langenhoe Hall Farm. The old cottage arrived at its unusual name through a strange old folk tale.

When the Lord God made the world, this was the last place He found out – and the owd Davvil was a-living here then.

This little shard of marshy land to the north of Mersea Island is the Devil’s country, and another story concerning the ‘Owd Davvil’ has him joining the twelve strong mowing gang as the thirteenth stranger called Hoppin’ Tom. This was originally recounted by marshman, adder-catcher, bull-tamer and poacher, Ted Allen, and was told something like this -

Once, long ago, a gang of twelve men was sent to mow Langenhoe Marsh, and very soon after they began work, a mysterious stranger surreptitiously joined them. The men were soon feeling irritated, as he mowed faster than any of them, and as a result, he earned much more money. Then one chap spied that he had cloven hooves and knew at once that he must be the Devil. Subsequently, the mowing gang formed a plan, and they had thrown down a load of iron bars in the long grass overnight. The following morning, ’the Owd Davvil’ mowed through the iron with ease, it was like they were made of butter. But later when he came to draw his pay, the farmer spied his hooves, and exclaimed “You’re the Davvil called Hoppin’ Tom, and I won’t pay you” and the Devil let out ‘a shrik like an owl and flew off in a sheet o’ flame’. As Tom flew off, he threw his drinking bowl into the field, and that’s why we still call the small pond the ‘Davvil’s Drink Bowl’ to this day. We never saw Hoppin Tom again after that; well not us, anyway.

Hidden within this old folk tale, we may have a folkloric echo that leads us into the secretive world of traditional marsh-magic, where twelve members met with the leader of their clan, to make the witchy number of thirteen. Perhaps it was on the very cusp of Langenhoe Marsh, that the leader of this mysterious group was once known as “The Owd Davvil Hoppin’ Tom”.

The above excerpts are taken from my recent book - The Liminal Shore: Witchcraft, Mystery & Folklore of the Essex Coast, published by Troy Books.

For more tales of witchcraft, mystery and magic of the Essex coast, please click the book cover, which will take you to my publishers website, where you can purchase a copy of The Liminal Shore

Photographs copyright Alex Langstone. Illustrations copyright Paul Atlas-Saunders.